In November 2010 when I was working as a Sociology Instructor at a Further Education College in the UK, I was lucky enough to get some time off to attend the 7th annual Open Education Conference, held that year in a beautiful science museum in Barcelona. At the time the Open Education movement was still relatively young and appeared, at least to me at the time, progressive and radical. I remember being wowed by presentations from the likes of Martin Weller, Paul Stacey, Richard Hall and Joss Winn, Rory McGreal and the late Erik Duval. Sessions referenced the University of the People and the University of Utopia, Manifestos for OER Sustainability, CloudWorks and OERopoly (a game to generate collective intelligence around OER). It felt exciting, cutting-edge, DIY and autonomous. There was talk of EduPunk and apparent schisms between those who promoted sustainability and funding models versus those who saw the potential of Open Education to initiate not just a revolution in teaching and learning but in society itself. It was exhilarating stuff.

Fast-forward seven years and thanks to my colleagues in the Library and Ed Tech I was able to attend the 14th annual Open Education Conference, this time held in Anaheim, California. One immediate difference was the size: 2010’s conference involved around 200 participants whereas estimates put this year’s attendance at well over 500 including what seemed to me to be large numbers of first-time attendees. Another was the format. In Barcelona we had keynotes and presentations mainly, whereas Anaheim added round-table discussions, an unconference session and a musical jam. Dialogue and conversations felt genuinely participatory, democratic and inclusive even though there was a recognition that much work still needs to be done in this area.

Fast-forward seven years and thanks to my colleagues in the Library and Ed Tech I was able to attend the 14th annual Open Education Conference, this time held in Anaheim, California. One immediate difference was the size: 2010’s conference involved around 200 participants whereas estimates put this year’s attendance at well over 500 including what seemed to me to be large numbers of first-time attendees. Another was the format. In Barcelona we had keynotes and presentations mainly, whereas Anaheim added round-table discussions, an unconference session and a musical jam. Dialogue and conversations felt genuinely participatory, democratic and inclusive even though there was a recognition that much work still needs to be done in this area.

The Keynotes

The originally announced Keynote line-up had received some criticism from a number of people on Twitter both for its lack of diversity and for including a representative of an organisation whose policies run counter to the ideals of the open education movement. Challenging this took a good deal of courage from those who stood up to be counted and from those who backed them. Encouragingly, the conference organiser took the criticisms on board and made some changes to the programme.

The originally announced Keynote line-up had received some criticism from a number of people on Twitter both for its lack of diversity and for including a representative of an organisation whose policies run counter to the ideals of the open education movement. Challenging this took a good deal of courage from those who stood up to be counted and from those who backed them. Encouragingly, the conference organiser took the criticisms on board and made some changes to the programme.

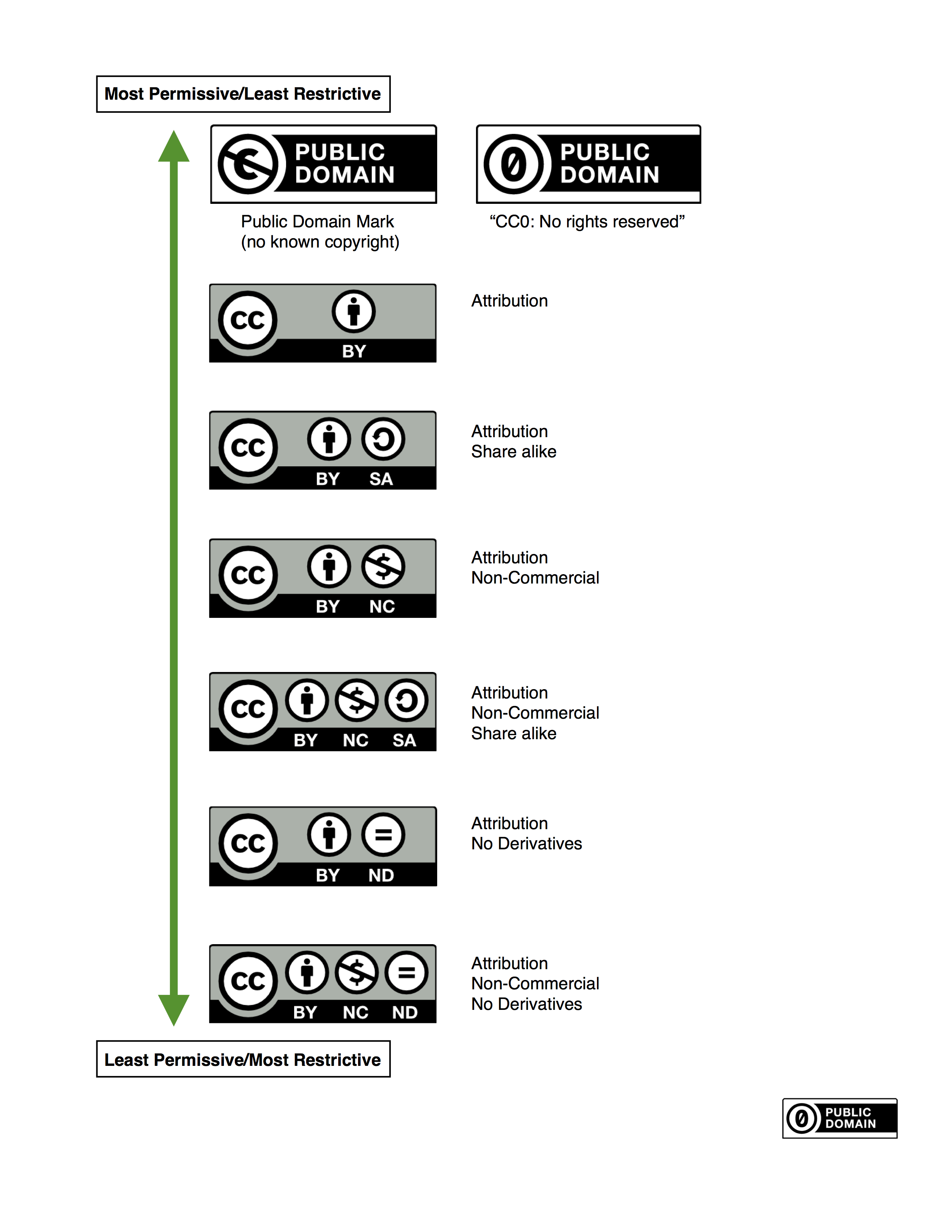

Ryan Merkely, CEO of Creative Commons kicked off Wednesday’s programme by announcing a prototype of a search tool that brings 1-click attribution as well as a new CC Global Network Open Education Platform which all open education advocates are invited to participate in. Ryan devoted the rest of his Keynote to presenting an intensely personal and powerful call for us to build the Open Ed community by focusing on values of equity, inclusivity and diversity. This process often requires us to listen to others, examine our own privilege and ensure that no voices are left out. In other words “Active, unrelenting inclusion” as Jamison Miller put it.

Friday morning’s Keynote Addresses were given by David Bollier and Cathy Casserly. Bollier, who is Director of the Reinventing the Commons Program at the Schumacher Center for a New Economics, urged us to see the knowledge commons as embodying a different set of values and practices to the global market and the state. Whereas global capital imposes social relationships of price, enclosure, patents and copyright, the commons is a self-organised social system that emphasises fairness, responsibility, long-term stewardship and meeting peoples’ basic needs. The next big thing, Bollier argued, could well be a lot of small things — examples such as Platform Co-operativism, community land trusts, makerspaces, and the various ‘opens’ (source, textbooks, journals) point the way to a new generative and value-creating movement beyond the tyranny of business models, bureaucracy and the market.

I first heard Cathy Casserly speak in Barcelona in 2010, back when she was about to become CEO of Creative Commons. She is an excellent speaker, and has the unique ability to tell personal stories and link them to wider political events. At its core, she argued, the Open Education movement is about freedom, transparency, social justice, equity, access and inclusion, values that are being fundamentally threatened in the current social and political climate. If we are to achieve our ambitious aim of transforming learning globally then we must grow, and as we grow reflect intently on the various ‘nodes’ within our network, ensuring all voices are included and given space for articulation. As we move from the “terrible twos” into our “teenage years” we must also think about issues of governance and leadership and consider giving a far more prominent role to Open advocates on the ground (those that “make shit happen” as Cathy put it). Otherwise the Open Ed movement could end up replicating the power structures of the traditional Taylorist model of education that it is trying to replace.

I first heard Cathy Casserly speak in Barcelona in 2010, back when she was about to become CEO of Creative Commons. She is an excellent speaker, and has the unique ability to tell personal stories and link them to wider political events. At its core, she argued, the Open Education movement is about freedom, transparency, social justice, equity, access and inclusion, values that are being fundamentally threatened in the current social and political climate. If we are to achieve our ambitious aim of transforming learning globally then we must grow, and as we grow reflect intently on the various ‘nodes’ within our network, ensuring all voices are included and given space for articulation. As we move from the “terrible twos” into our “teenage years” we must also think about issues of governance and leadership and consider giving a far more prominent role to Open advocates on the ground (those that “make shit happen” as Cathy put it). Otherwise the Open Ed movement could end up replicating the power structures of the traditional Taylorist model of education that it is trying to replace.

What about the students? In part two of this blog post I will switch attention to an inspiring panel involving students from a local college, reflect on my presentation on international student engagement with open textbooks, and talk about some of the technologies and platforms that are being promoted as open alternatives to proprietary software from the likes of Pearson and McGraw-Hill.